Equal on Land and Sea: Margaret Brown, Feminism, John Jacob Astor IV, and My Weird Writing Life

2024 marks the 112th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic on her first voyage. It was a tragic event, and one that we have been obsessed with ever since.

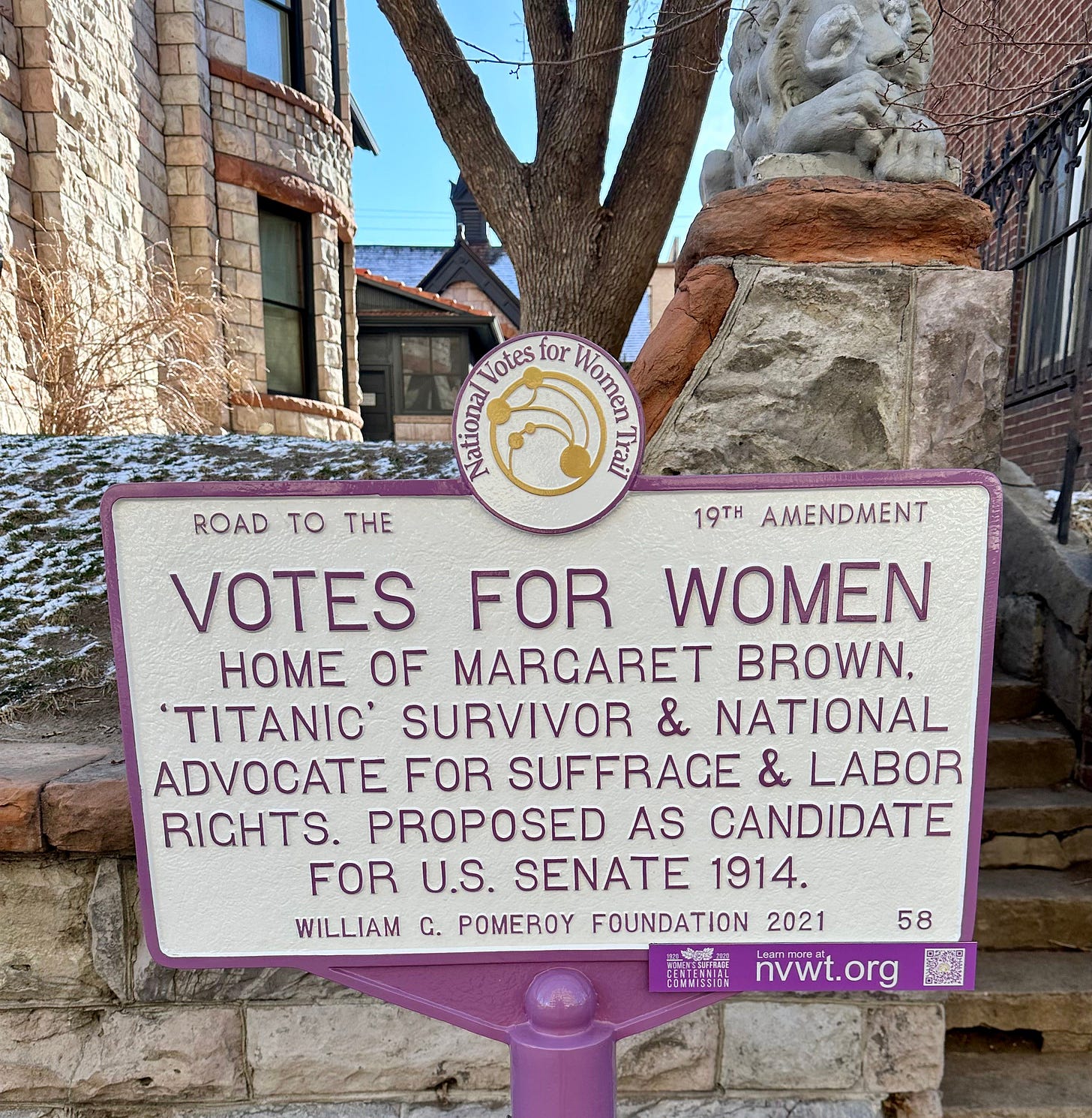

I’ve been obsessed, too. The sinking plays a big part in my first book, Molly Brown: Unraveling the Myth, and unexpectedly in my forthcoming book, Friend and Faithful Stranger: Nikola Tesla in the Gilded Age. Margaret Brown famously survived the Titanic sinking (she was never known as “Molly”!), and John Jacob Astor IV, who famously did not survive, was one of Nikola Tesla’s greatest friends and benefactors.

My writing life has a funny way of making things connect. It turns out that Margaret Brown and her daughter Helen were hanging out together with the Astors in Egypt before they boarded the Titanic. (Yes, there are photos of camels and pyramids!) John Jacob and his new wife, Madeleine, were on their honeymoon, eager to get away from New York society which had vilified them. “Jack” Astor was legally divorced, but the church had a problem with his remarriage, and proper society thought his new wife was much too young. (On their wedding day, she was 18 and he was 47.)

When Madeleine became pregnant, the couple decided to curtail their honeymoon and get back to the states as quickly as possible. They booked the Titanic. Margaret Brown received a telegram from her son Lawrence that her new grandson was ill. She booked the Titanic. Daughter Helen decided to stay behind in Paris (good call).

Everyone knows the story. On April 10, 1912, when Titanic set sail from Southampton, England, for New York City, the White Star Line boasted that the largest passenger steamship ever built “could never sink.” At 11:40 PM, not long after dinner, the crew spotted an iceberg. Three hours later, the ship sank. Of the 2,223 people aboard, 1,517 died.

Both Margaret Brown and Jack Astor became heroes in the press for very different reasons. Margaret was picked up by the back of her neck and dropped into lifeboat number six, and went on to cheer on her fellow rowers, help survivors – many of them immigrants – on the rescue ship Carpathia, and look after them when they docked, anguished and exhausted, in New York. “Feeling a duty to remain after the army of Red Cross doctors and nurses, White Star officials, and general Aid Corps [primarily the Travelers Aid Society] had taken leave of the ship, we found it was necessary to improvise beds in the lounge, so I remained with them on board the Carpathia all night,” she said. “There were many who had friends on the dock, but did not know them, so with each one was sent an escort and the names called out.” As a symbol of gratitude, Margaret later presented a special trophy from the Titanic survivors to Captain Rostron and crew of the rescue ship Carpathia. Her feet and legs never recovered from those long hours spent in waist-high freezing water.

Jack Astor met a different fate. He helped others into lifeboats, and when it was Madeleine’s turn, he politely asked an officer if he might accompany her as she was in a “delicate condition.” Madeleine was 19 years old and five months pregnant. His request was denied. Days later, Vincent Astor, his 21-year-old son from his first marriage, identified the body.

But for now, back to Margaret. Although she was not allowed to testify at the Titanic hearings (like other women), she had a lot to say about the subject. She wrote a lengthy article, “The Sailing of the Ill-Fated Steamship Titanic,” in the Newport Herald (May, 28, 29, and 30, 1912). And in Denver, she was a star. Mrs. Crawford Hill, prominent Denver socialite, hosted a luncheon in her honor. To the Denver Times Margaret said, “I think I have been misrepresented to my Denver friends. I simply did my duty as I saw it. I knew that I was healthy and strong and was able to nurse the suffering. I am sure that there was nothing I did throughout the whole affair that anyone else wouldn’t have done. That I did help some, I am thankful and my only regret is that I could not have assisted more.” She held her position as chair of the Survivors’ Committee until her death twenty years later.

Margaret didn’t stop there. A prominent feminist and co-founder of the Woman’s Party, she spoke out about unfair gender stereotypes. “They told me of the navigation laws restricting men from the boats when women and children were on board,” Margaret wrote. “I replied that such must have been the ancient law, and now that equal rights existed … their conscience on that score should be relieved.” The greatest tragedy of the Titanic, in Margaret’s opinion, was that families were needlessly separated. “‘Women first’ is a principle as deep-rooted in man’s being as the sea,” she stated. “It is world-old and irrevocable. But to me it is all wrong. Women demand equal rights on land—why not on sea?”

The gender debate raged in the newspapers, from the pulpits, in drawing rooms and street pubs. Margaret snapped at a reporter, “I wonder if I make myself understood? What I mean is that many men went down with the ship who should have saved themselves for their families’ sakes. I do not condemn the men utterly for doing what by education and training they have been made to consider themselves irrevocably bound to do, but I say it is a false standard of conduct they adhere to and, analyzed to the bottom, it means nothing but selfishness. Consider those widows left behind... and women whose husbands and children were with them should have held back and declined to be saved.”

Margaret succinctly summed things up with this comment: “The Titanic disaster,” she said, “was a tragedy that was as unnecessary as running the Brown Palace Hotel into Pike’s Peak.”

For more information on Margaret Tobin Brown, see my book Molly Brown: Unraveling the Myth.

For more on John Jacob Astor IV and Nikola Tesla, stay tuned!

And thanks again for reading!

If you’d like to comment or gain access to all my archives as well as find specific content just for writers, consider upgrading to a premium subscription.