This week I’m going to talk about a subject that is near and dear to me, one that falls under the general category of the “Ethics of Literary Nonfiction” (who knows, perhaps this series will turn into a book!). This will be part one of two parts. This week I’m going to talk about memoir, and in part two I will talk about biography, and literary biography in particular.

Between these two posts I will be writing from Serbia. I’m very excited to be traveling to Belgrade this week to deliver a short talk on the life of Nikola Tesla for the International "Days of Nikola Tesla 2024" Conference at Kolarac University. Tesla spent most of his life in New York, and this presentation will focus on the places and the people Tesla loved in New York City, including his laboratories, the hotels where he lived, his favorite restaurants and clubs, and the streets and parks where he daily walked. I’ll be posting more about this as we draw nearer to the publication date for Friend and Faithful Stranger: Nikola Tesla in the Gilded Age.

But for now, back to the thorny and powerful subject of memoir.

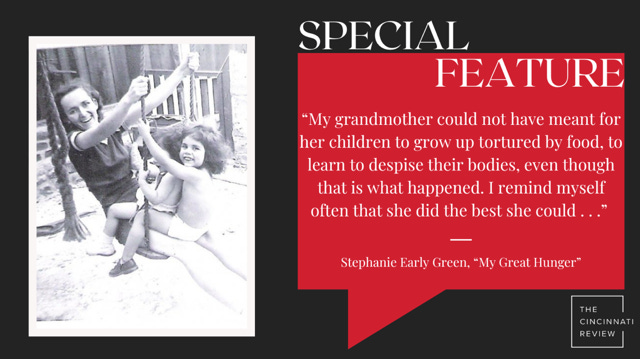

Recently, at the Cincinnati Review, we had the opportunity to publish a special feature, a remarkable essay, “My Great Hunger,” by Stephanie Early Green. This essay explores the notion of generational family trauma, and how it affects families, individuals, and the physical body in particular. It is a compelling and very thought-provoking read. It takes a brave writer to discuss topics as personal and powerful as this – and this is the kind of essay that can be transformational.

As often happens in this kind of situation, despite an overwhelmingly positive response from readers and most of the author’s family members, a couple of family members criticized the author for daring to write an essay like this. And – again, as often happens – the justifications for this type of criticism tend to sound the same: Let sleeping dogs lie. It didn’t really happen the way you think it did. Let’s just put a positive spin on everything. Let’s pretend certain things never happened. Everything is fine.Who gives you the right to write this story?

First, let me emphasize: You have the right to tell your story. And even if you tried to write an essay that would “please” everyone, be “approved” by everyone – well, that’s obviously impossible.

The best and only thing to do is to write as truthfully, and beautifully, as you can.

This is certainly an issue I’ve faced many times in my own writing life, and it is a common challenge for writers, and writers of memoir in particular. But again: It’s only by telling the full truth, by seeking empathy and understanding about often painful events, that true insight can happen. True stories can change lives, they can change families, they can change communities. Let me give you an example.

When I wrote Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Shadow of Rocky Flats, I received pushback from all kinds of places. A blend of memoir and investigative journalism, this book revealed and explored the secret and suppressed history of the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant. I grew up just down the road from that notorious place, and later I worked there myself. When I wrote the book, many people said it would never get published. Cold War secrets and bomb production contamination should never be revealed to the public. This is a dangerous and even shameful part of our history. Let the past stay in the past.

The other part of the story had to do with the secrets and silencing in my own family, particularly related to my father‘s alcoholism. My father was a brilliant man but he struggled with his own demons. He essentially lost his law practice, and his family, through his alcoholism. It is a sad story, but a poignant one, and it is a generational story. It turns out that alcoholism runs in both sides of my family, which is a topic no one really wants to talk about. The effects of these things are felt at the level of the individual, the family, and the community, often for generations.

My father read the book before it was published and was well aware of it, but I don’t think it really struck him that book was real until it was on the shelves of bookstores. My dad and I had never been close; nevertheless I was concerned and apprehensive about his response. But the book turned out to be transformational, and in a way that was quite surprising to me.

Indeed, my father, and a couple of other family members, were upset that I had not only exposed what was going on at Rocky Flats, where many of our family friends had worked, but I had also chosen to write about our big family secret: alcoholism. My mother used to say, “These are things we don’t talk about. These are things no one should know. Let’s keep this to ourselves.”

I will never forget the morning in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where I was staying to do a reading at a local bookstore. My father called me. It may have been the first time that he ever actually called me. He said, “Come see me.” So when I got back to Denver, I did. He was in poor health, but we talked. Perhaps really talked, for the first time ever.

Was he able to really face what had happened? Did he really understand the story I was telling? I don’t know. But I know that we connected. And a short time later, just before he passed, my sisters and I were at his bedside. I held his hand and stroked his forehead.

Full Body Burden impacted my family, and my community, and the way we tell the history of the Cold War, in ways I never could have anticipated. Telling true stories can, indeed, help change the world.

So I was very happy, a few days ago, to receive an email from Stephanie Early Green. A family member had unearthed a letter from decades ago that confirmed the stories in her essay.

We take risks when we write memoir and talk about our experiences, our families, our joys and sorrows. But it is a worthy risk.

In the next post, I will talk about writing biography and the challenges of writing about the lives of others.

In the meantime, I’m off to Serbia! Thanks for reading.

Thank you Kristen for this welcome reminder that a) our stories--even those we make up about other people--are ours to tell, and b) there will always be others who don't like, don't approve of, and speak ill of what we do. C'est a vie, eh? I recently found a photo of you and me smiling in our caps and gowns at my graduation from SJSU 2002. To be your student was a measureless joy. Appreciatively, A.T. Lynne (aka Lynne Wilkinson)